A Millennial’s Perspective

This editorial is written by Christina Kelly, a 30-year-old practitioner who began her aikido journey six months ago. Christina, a Harvard graduate, has written editorial for leading media companies such as ESPN and Blizzard Entertainment. This is a story about hope, compassion, and the importance of aikido’s spirit of peaceful reconciliation.

We are in the middle of a very interesting time in human history. It’s true that violence overall has declined massively from the days of human sacrifice and laws that enshrined dueling to the death as a legitimate way to resolve grievances. However, we still find ourselves in a world where it seems harder and harder to communicate and collaborate with people who don’t share our views, and where people can still become victims through no fault of their own via terrorist attacks or bombs that were not carefully deployed in wars.

The human race desperately needs a philosophy that can teach us empathy for each other and demonstrates that even adversaries can work together for a greater good. In other words, it’s the

perfect time for aikido to shine.

Why Aikido?

As a 30-year-old first dan black belt in taekwondo, a more conventional punch-and-kick kind of martial art, I initially felt out of my element when I started training in aikido six months ago. Why were we learning about the subtleties of skeletal joints and the muscular system? Why were we practicing five different ways to fall out of a throw? Why were we trying to close the distance to our opponents and adopt a “flow” style of technique rather than standing firm against them?

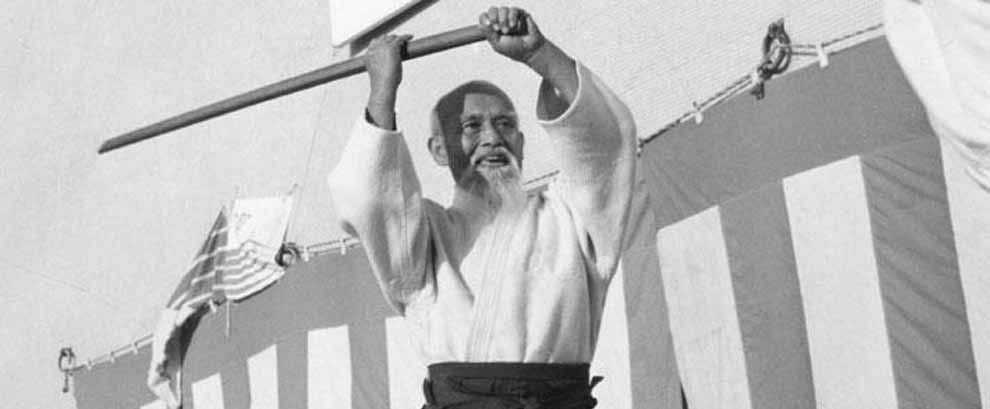

The answer came when I started researching the origins of aikido. From my longtime study of the Chinese language and writing system, I saw that the term “aikido” in kanji translated to something like “the way of uniting forces,” where the forces that were being united weren’t those of best friends or even regular strangers, but two opponents potentially engaging in physical combat. It turns out that it takes a fair amount of knowledge of anatomy and physics to determine how to safely position oneself against and attacker and be in a position to employ a technique. Dado que este conocimiento solo se puede obtener a través de la experiencia,,en,tiene sentido que los practicantes de aikido unan fuerzas para mostrarse mutuamente cómo aplicar técnicas en varios tipos de personas,,en,No se tu,,en,pero si alguien amenazó con atacarme físicamente,,en,lo último en mi mente sería la idea de unir fuerzas con ellos,,en,incluso si prefiero ser amigo de alguien que enemigo,,en,Y todavía,,en,el aikido enseña que este concepto es la clave para una defensa personal efectiva,,en,tanto en la práctica como en el mundo real,,en,En este marco,,en,el éxito no se trataba solo de deshabilitar a un oponente rápidamente,,en,pero hacerlo de la manera más humana posible,,en,Se necesita mucho trabajo extra para hacerlo bien,,en, it makes sense that aikido practitioners join forces to show each other how to apply techniques on various kinds of people.

I don’t know about you, but if someone threatened to attack me physically, the last thing on my mind would be the idea of uniting forces with them, even if I’d rather be friends with someone than enemies. And yet, aikido teaches that this concept is the key to effective self-defense, both in practice and in the real world. In this framework, success wasn’t just about disabling an opponent quickly, but doing it in the most humane way possible. It takes a lot of extra work to do it right, but it leaves the door open for reconciliation and understanding when an attacker realizes that you’re going the distance to prevent serious harm to them.

Últimos Comentarios